Remembering James Chaney

Everyone knows James Chaney, the civil rights martyr. Fewer remember James Chaney, the civil rights activist.

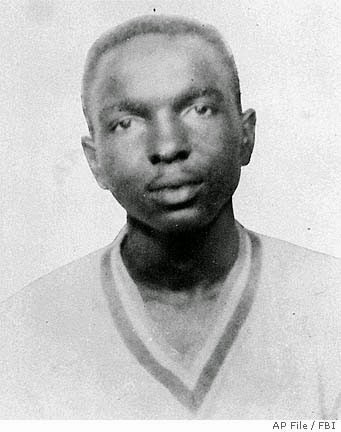

James Chaney

James Chaney

James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were murdered by a mob of Klansmen in Neshoba County, Miss. on June 21, 1964. For 44 days, hundreds of FBI agents and Navy sailors searched for the missing civil rights workers, until their bodies were found on August 4, buried in an earthen damn. During the massive hunt for the slain young men, Rita Schwerner, Michael’s young widow, said, “We all know that this search with hundreds of sailors is because Andrew Goodman and my husband are white. If only Chaney was involved, nothing would’ve been done.”

After reading and writing about these murders for 10 years, one thing that strikes me this year is that the whiteness of two of the victims continues to play a role in our perceptions.

Without white people among the victims, James Chaney’s death would not have been important to authorities or the country at large. But with the white victims present there is a tendency in memorializations to overlook Chaney’s humanity—to remember him only as the black victim rather than as a person who contributed tirelessly to the civil rights movement.

The roles that the three civil rights workers were playing in the freedom struggle are generally not heavily emphasized today, but recollections tend to include that Andrew Goodman was arriving in Mississippi as a Freedom Summer volunteer and that Michael and Rita Schwerner were running a CORE community center in Meridian, Miss. But what about the civil rights work of James Chaney?

As a small corrective to this myopia, here are some passages from white southern journalist William Bradford Huie’s Three Lives for Mississippi, originally published in 1965 and still essential reading on Neshoba murders.

CORE workers Michael Schwerner, Rita Schwerner and Lenora Thurmond, wrote to the national office of CORE on April 23, 1964 to request that James Chaney be hired as staff at the Meridian community center where they all worked.

We’re writing to ask a favor. We know that CORE is short of funds, and therefore we debated a long time before bringing up this subject … but we feel that it is important. We would like to implore the National Office to place a young man on field staff.

James Chaney is 21 and a native of Meridian. Since the office was established here, long before any of the three of us arrived in town, he has been working full time, doing whatever work was necessary. When he started to get the community center in order, James worked with Mick building shelves, loading books, painting. He has canvassed, set up meetings, gone out into some of the rough rural counties to make contacts for us. Tonite he is running a mass meeting here in Meridian. In short, there is no distinction in our minds or his as to the amount of work he should do as a volunteer, and we as paid staff. We consider James part of the Meridian staff, and he is in on all major decisions which are made here.

In February, when there was so much work to be done in Canton, Matt Suarez asked for help and James went. He worked in Canton for almost a month, helping to organize for Freedom Day. He spent about a week in Greenwood, prior to the Freedom Day there. He was sent into Carthage, and would have continued to do voter registration work there, though only a volunteer, had it not been decided to temporarily abandon that spot.

James has never so much as asked us to buy him a cup of coffee, though he has no means of support. We believe that since he long ago accepted the responsibilities of a CORE staff person, he should be given now the rights and privileges which go along with the job.

Thank you for listening to our request…

For freedom,

(signed) Rita and Mike Schwerner

Lenora Thurmond

According to Marvin Rich, a CORE representative who traveled among and evaluated the work of the local community projects,

On this trip I made to Louisiana and to Jackson, Canton and Meridian, Mississippi, there were requests for additional staff from each community. Chaney was the only one hired.

Sue Brown was one of the first African Americans from Meridian to work for CORE. She introduced James Chaney to Matt Suarez in 1963, which led to Chaney’s ongoing presence at the Meridian community center. It was Brown who was making the initial phone calls on June 21, 1964 to inform the state COFO offices and the FBI that Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman had not returned from Neshoba County and had not been heard from.

I remember seeing him in high school before he dropped out. He was the typical young Mississippi Negro, from a broken home, who becomes a dropout. His father was gone; his mother had five children; and they all tried to do what they could to keep bread on the table. He didn’t have much to say, and he always walked with his head down. He did odd jobs, like a painter’s helper or a carpenter’s helper. He knew he wasn’t going anywhere. His speech was crude: he used words like ain’t. So he was the kind the Movement means everything to. He got so he could get up before a small crowd and urge them to join the Movement. He’d go hungry and do all the dirty work, just for the chance to stay around the Center where he felt like something was going on. I guess with the Movement he found his first sense of participation. Mickey knew how to put him at his ease, so Mickey could count on Jim Chaney to walk through hell with him.

And walk through hell James Chaney did. But he had already given his life to the Movement many months before he was murdered, and for this he should also be remembered.

Further Reading

- We Are Not Afraid: The Story of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney, and the Civil Rights Campaign for Mississippi, by Seth Cagin and Philip Dray, includes extended passages about Chaney’s life before and during his time with CORE.

- Edgar Ray Killen Needs Some Company, a hungryblues.net post, in which the Steele family, from the Longdale community in Neshoba County, remembers Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman.

- Podcast: Interview with Ben Chaney, a 10 minute hungryblues.net interview with James Chaney’s younger brother Ben from 2007.